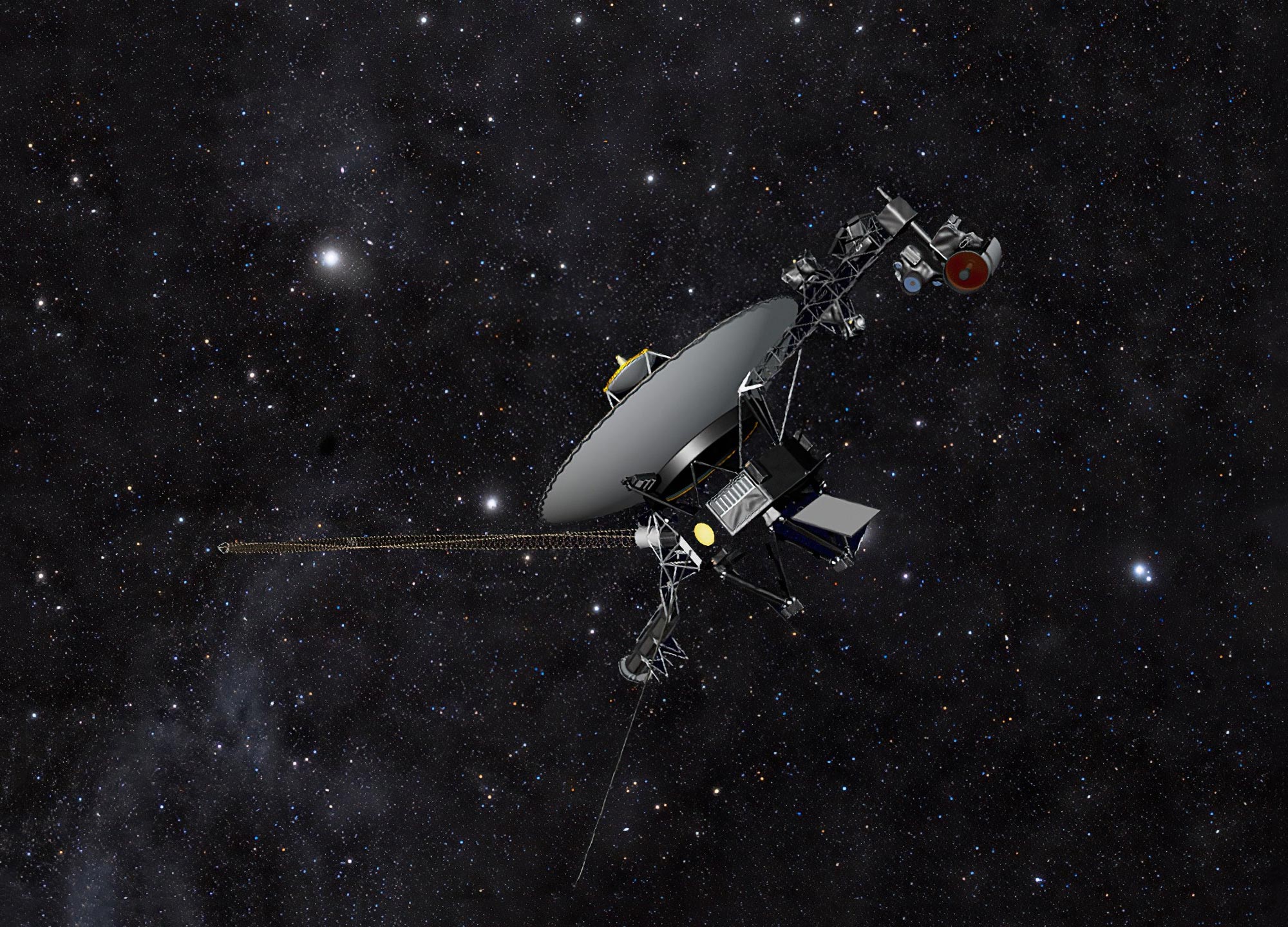

Koncept tohoto umělce ukazuje kosmickou loď Voyager NASA proti poli hvězd v temnotě vesmíru. Dvě kosmické lodě Voyager cestují stále dále a dále od Země, na cestě do mezihvězdného prostoru a nakonec budou obíhat kolem středu Mléčné dráhy. Poděkování: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Tento plán udrží vědecké přístroje Voyageru 2 v provozu o několik let déle, než se původně očekávalo, což umožní další objevy z mezihvězdného prostoru.

Sonda Voyager 2, která byla vypuštěna v roce 1977, je od Země vzdálena více než 12 miliard mil (20 miliard kilometrů) a využívá pět vědeckých přístrojů ke studiu mezihvězdného prostoru. Aby pomohla udržet tyto přístroje v chodu navzdory ubývajícím zdrojům energie, začala stárnoucí kosmická loď používat malý rezervoár záložní energie, který byl vyčleněn jako součást palubního bezpečnostního mechanismu. Tento krok by umožnil misi odložit uzavření vědeckého nástroje až do roku 2026, namísto letošního roku.

Vypnutím vědeckého přístroje se práce nedokončí. Po vypnutí jednoho přístroje v roce 2026 bude sonda nadále napájet čtyři vědecké přístroje, dokud si nízký zdroj energie nevyžádá vypnutí dalšího. Pokud Voyager 2 zůstane zdravý, inženýrský tým očekává, že mise bude pokračovat i v nadcházejících letech.

Důkazní testovací model Voyageru, vystavený ve vesmírné simulační místnosti v JPL v roce 1976, byl přesnou replikou dvou kosmických sond Voyager vypuštěných v roce 1977. Měřicí platforma modelu se rozprostírá napravo a drží několik vědeckých přístrojů kosmické lodi při publikování. . pozice. Poděkování: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Voyager 2 a jeho dvojče, Voyager 1, jsou jediné dvě kosmické lodi, které operují mimo heliosféru, ochrannou bublinu částic a magnetických polí generovaných Sluncem. Sondy pomáhají vědcům odpovědět na otázky o tvaru heliosféry a roli při ochraně Země před energetickými částicemi a dalším zářením v mezihvězdném prostředí.

řekla Linda Spilker, vědecká pracovnice projektu Voyager[{“ attribute=““>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes power themselves with radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. The continual decay process means the generator produces slightly less power each year. So far, the declining power supply hasn’t impacted the mission’s science output, but to compensate for the loss, engineers have turned off heaters and other systems that are not essential to keeping the spacecraft flying.

With those options now exhausted on Voyager 2, one of the spacecraft’s five science instruments was next on their list. (Voyager 1 is operating one less science instrument than its twin because an instrument failed early in the mission. As a result, the decision about whether to turn off an instrument on Voyager 1 won’t come until sometime next year.)

Each of NASA’s Voyager probes are equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), including the one shown here. The RTGs provide power for the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In search of a way to avoid shutting down a Voyager 2 science instrument, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the instruments in case the spacecraft’s voltage – the flow of electricity – changes significantly. Because a fluctuation in voltage could damage the instruments, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that triggers a backup circuit in such an event. The circuit can access a small amount of power from the RTG that’s set aside for this purpose. Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating.

Although the spacecraft’s voltage will not be tightly regulated as a result, even after more than 45 years in flight, the electrical systems on both probes remain relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team is also able to monitor the voltage and respond if it fluctuates too much. If the new approach works well for Voyager 2, the team may implement it on Voyager 1 as well.

“Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we’ve determined that it’s a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at JPL. “We’ve been monitoring the spacecraft for a few weeks, and it seems like this new approach is working.”

The Voyager mission was originally scheduled to last only four years, sending both probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the boundary in 2012, while Voyager 2 (traveling slower and in a different direction than its twin) reached it in 2018.

More About the Mission

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of Caltech in Pasadena, built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

Přátelský webový obhájce. Odborník na popkulturu. Bacon ninja. Tvrdý twitterový učenec.